Tuesday, February 27, 2007

Monday, February 26, 2007

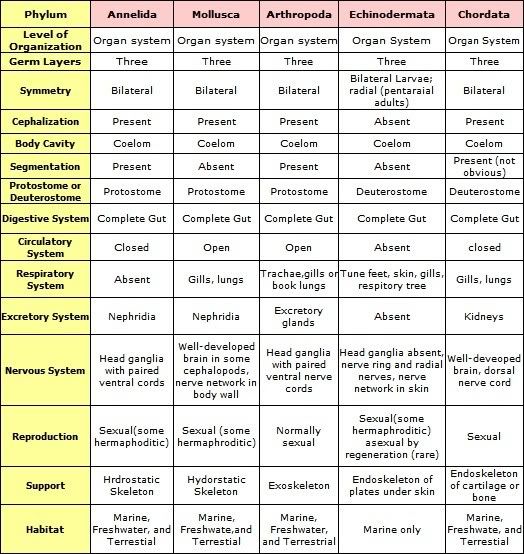

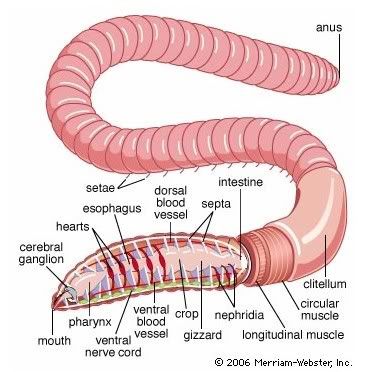

General Anatomy

Habitat

All annelids use their habitat primarily for food or shelter. Many species use the ground to burrow for safety, and many polychaetes are tube-dwellers, who burrow into tubes found in the muddy bottom of the ocean or beaches. Still others actually eat their habitats. Called non-selective deposit feeders, these annelids eat mud, sand, or soil. The organic matter is then digested; however, since the amount of nutrition gained by this type of feeding is quite small, non-selective deposit feeders must eat almost continuously.

Annelids are found world-wide. Nearly 2/3 of the known annelids falls under the Class Polychaetes and are typically marine organisms. These marine worms can be found anywhere from shallow beach waters to deep ocean trenches. The remaining 1/3 of the Class Polychaetes can be found in freshwater and very moist land. Another class of annelid worms is the Oligochaeta. Oligochaeta are typically found on land or in freshwater; these are the worms that people usually associate with “segmented worms”, such as earthworms. The last class, Hirundinea, is typically comprised of freshwater dwellers; however, there are a few land and marine species. Hirundinea includes animals such as leeches.

Vocabulary:

Annelid: round wormlike animal that has a long segmented body and belongs to the phylum annelida

Polychaetes: segmented worm usually marine characterized by paired paddle like appendages on its body segments and a bristly body

Oligochaeta: Annelid worm belonging to the class that contains common earthworm and related species that live in soil and in water

Leech: annelid worm that typically exists as an external parasite that drinks the blood and body fluids of its host

Longitudinal muscles: runs for the front of the worm to the rear. When these muscle contact they make the worm skinnier

Clitellum: it secretes a mucus ring into which egg and sperm are released.

Pharynx: muscular front end of the digestive tube which can be extend to catch food

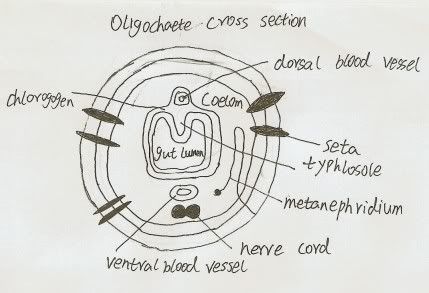

Circulatory/Internal Transport:

The circulatory system varies among the different members of annelids. Most have blood with hemoglobin, a red pigment that carries oxygen, but some others have a green pigment that carries oxygen, or unpigmented blood. Most segmented worms (such as earthworms) have a closed circulatory system which means the blood circulates only within a system of blood vessels, rather than mixing with fluid in the body cavity. In each of the segments in the body of the annelid, there is a pair of smaller vessels called ring vessels. The ring vessels connect the dorsal and ventral vessels of the annelid and supply blood to some small internal organs and transports blood from the anterior to the posterior. There are 10 main ring vessels located on top of the gut that serve as hearts. In leeches, the closed circulatory system is reduced or absent and it may be replaced by coelomic canals. In other annelids, blood is helped moved around the body by muscle contractions when the annelid is moving itself.

The leech’s pharynx is used to suck blood.

Anatomy of an Earthworm

Feeding:

Feeding styles vary from eating organic material that settles on the surface of the muddy substrate (detritus feeding), to filtering plankton, sucking blood out of other animals (parasitic) and detritus from the water using feathery feeding tentacles (suspension feeding), to eating their neighbors (predation).

The filter feeder plume worm

Digestion:

Segmented worms have a gut that runs the length of the body, and is separated from the body wall by the coelom. Food enters the mouth and travels through the gut, where it is digested. An important feeding organ that has evolved in most annelids is the pharynx. The pharynx is the muscular front end of the digestive system. In carnivorous annelids, such as the sandworm, the pharynx has two or more sharp jaws which are useful for capturing prey. Herbivores also have this jaw used for tearing algae. In detritus feeders, such as earthworms, the pharynx acts as a pump to allow water and soil enter the earthworm. In parasites, such as leeches, the pharynx is used to suck blood out of its host. In the some filter feeder annelids, they use their long tube like burrows to catch passing algae in the ocean.

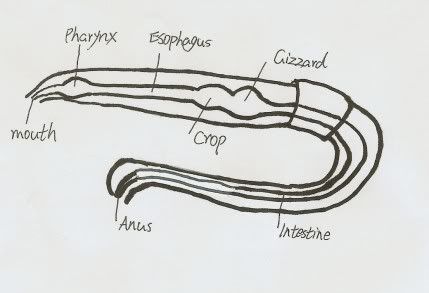

Excretion:

Annelids produce two types of wastes—solid and liquid. Solid wastes are removed from the gut through the anus and liquid wastes are removed by tube-shaped oranges called nephridia. These organs act very similar to kidneys and remove urea. A pair of nephirdia are present in each body segment and removes waste products from body fluids and excretes them.

Cites:

Biology textbook

http://www.tolweb.org/articles/?article_id=57

http://ebiomedia.com/prod/BOanelids.html

Leech:

http://biodidac.bio.uottawa.ca

Earthworm anatomy:

http://concise.britannica.com

Plume worm:

http://www.ryanphotographic.com

Monday, February 19, 2007

Respiration:

Annelids have no lungs, but many have gills for respiration. Respiration occurs by diffusion through the moist surface of the body. That's why earthworms die so quickly when their epidermis dries up. Most polychaetes also have gills to aid in respiration.

Response to the environment/Movement:

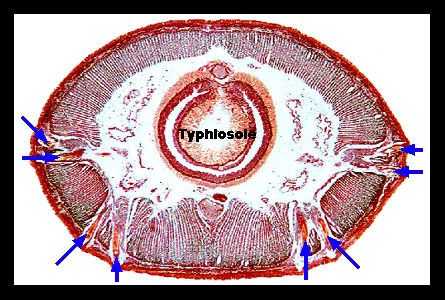

Annelids have various muscle groups and simple appendages. They use setae and parapodia for movement. Annelids such as the earthworm and the Lumbricus possess setae. A seta is a stiff hair, bristle, or bristle-like part of an organism. The setae are able to move in and out from the body wall. When the setae are withdrawn, the body extends, and the worm moves forward. Setae help earthworms attach to the surface and prevent backsliding during peristaltic motion. Parapodia (para = like; pod = foot) are mostly found in polychaetes and can extend and retract. Parapodia are paired, lateral appendages extending from the body segements.

Setae shown on the cross-section of a Lumbricus terrestris

Reproduction:

Annelids can reproduce asexually and sexually depending on the type of species.

Asexual Reproduction:

Asexual reproduction is by fragmentation, budding, or fission. Fission allows Annelids to reproduce quickly. The posterior part of the body breaks off and forms a new individual. For example, Lumbriculus and Aulophorus, are known to reproduce by the body breaking into such fragments. Many other species (such as most earthworms) cannot reproduce this way, though they have varying abilities to regrow amputated segments.

Lumbriculus variegatus

Sexual Reproduction:

Hermaphodites are common within Annelids, but others have seperate genders. Sexual reproduction allows a species to better adapt to its environment. Fertilized eggs of marine annelids usually develop into free-swimming larvae. Most polychaete worms have separate males and females and external fertilization. The earliest larval stage, which is lost in some groups, is a ciliated trochophore (type of larva with several bands of cilia), similar to those found in other phyla. The animal then begins to develop its segments, one after another, until it reaches its adult size.

Earthworms and other oligochaetes, as well as the leeches, are hermaphroditic and mate periodically throughout the year by copulation. Two worms lay their bodies together with their heads pointing opposite directions and sperm is transferred from the male pore to the other worm. Other methods of sperm transference have been observed in other genera and may involve internal spermathecae (sperm storing chambers) or spermatophores that are attached to the outside of the other worm's body. The embryonic worms develops in a fluid-filled "cocoon" secreted by the clitellum (a thickened glandular section of the body wall that secretes a viscid sac in which the eggs are deposited).

The clitellum on an Earth worm

http://library.thinkquest.org/28751/review/animals/5.html

http://www.biologyreference.com/Mo-Nu/Nervous-Systems.html

http://userwww.sfsu.edu/~biol240/labs/lab_17hydrostaticsk/

pages/annelid.html